I've found Ray Dalio's book Principles incredibly insightful. One area was around the use of technology for decision making.

Dalio first sets the stage for the relevant principles in sharing his life story. I've pulled out a few passages and emphasized things I found particularly interesting.

From very early on, whenever I took a position in the markets, I wrote down the criteria I used to make my decision. Then, when I closed out a trade, I could reflect on how well these criteria had worked. It occurred to me that if I wrote those criteria into formulas (now more fashionably called algorithms) and then ran historical data through them, I could test how well my rules would have worked in the past. ...

We tested the systems going as far back as we could, typically more than a century, in every country for which we had data, which gave me great perspective on how the economic/market machine worked through time and how to bet on it. Doing this helped educate me and led me to refine my criteria so they were timeless and universal. Once I vetted those relationships, I could run data through the systems as it flowed at us in real time and the computer could work just as my brain worked in processing it and making decisions.

The result was Bridgewater’s original interest rate, stock, currencies, and precious metals systems, which we then combined into one system for managing our portfolio of bets. Our system was like an EKG on the economy’s vital signs; as they changed, we changed our positions. However, rather than blindly following the computer’s recommendations, I would have the computer work in parallel with my own analysis and then compare the two. When the computer’s decision was different from mine, I would examine why. Most of the time, it was because I had overlooked something. In those cases, the computer taught me. But sometimes I would think about some new criteria my system would’ve missed, so I would then teach the computer. We helped each other. It didn’t take long before the computer, with its tremendous processing power, was much more effective than me. This was great, because it was like having a chess grandmaster helping me plot my moves, except this player operated according to a set of criteria that I understood and believed were logical, so there was no reason for us to ever fundamentally disagree.

The computer was much better than my brain in “thinking” about many things at once, and it could do it more precisely, more rapidly, and less emotionally. And, because it had such a great memory, it could do a better job of compounding my knowledge and the knowledge of the people I worked with as Bridgewater grew. ...

Of course, we always had the freedom to override the system, which we did less than 2 percent of the time—mostly to take money off the table during extraordinary events that weren’t programmed, like the World Trade Center going down on 9/11. While the computer was much better than our brains in many ways, it didn’t have the imagination, understanding, and logic that we did. That’s why our brains working with the computer made such a great partnership.

...

Over the last three decades of building these systems we have incorporated many more types of rules that direct every aspect of our trading. Now, as real-time data is released, our computers parse information from over 100 million datasets and give detailed instructions to other computers in ways that make logical sense to me. If I didn’t have these systems, I’d probably be broke or dead from the stress of trying so hard. We certainly wouldn’t have done as well in the markets as we have. As you will see later, I am now developing similar systems to help us make management decisions. I believe one of the most valuable things you can do to improve your decision making is to think through your principles for making decisions, write them out in both words and computer algorithms, back-test them if possible, and use them on a real-time basis to run in parallel with your brain’s decision making.

Dalio then articulates the specific principles in "Life Principles #5: Learn How to Make Decisions Effectively."

Life Principle 5.11: Convert your principles into algorithms and have the computer make decisions alongside you.

If you can do that, you will take the power of your decision making to a whole other level. In many cases, you will be able to test how that principle would have worked in the past or in various situations that will help you refine it, and in all cases, it will allow you to compound your understanding to a degree that would otherwise be impossible. It will also take emotion out of the equation. ... By developing a partnership with your computer alter ego in which you teach each other and each do what you do best, you will be much more powerful than if you went about your decision making alone. The computer will also be your link to great collective decision making, which is far more powerful than individual decision making, and will almost certainly advance the evolution of our species.

Life Principles 5.12: Be cautious about trusting AI without having deep understanding.

I worry about the dangers of AI in cases where users accept—or, worse, act upon—the cause-effect relationships presumed in algorithms produced by machine learning without understanding them deeply.

Before I explain why, I want to clarify my terms. “Artificial intelligence” and “machine learning” are words that are thrown around casually and often used as synonyms, even though they are quite different. I categorize what is going on in the world of computer-aided decision making under three broad types: expert systems, mimicking, and data mining (these categories are mine and not the ones in common use in the technology world).

Expert systems are what we use at Bridgewater, where designers specify criteria based on their logical understandings of a set of cause-effect relationships, and then see how different scenarios would emerge under different circumstances.

But computers can also observe patterns and apply them in their decision making without having any understanding of the logic behind them. I call such an approach “mimicking.” This can be effective when the same things happen reliably over and over again and are not subject to change, such as in a game bounded by hard-and-fast rules. But in the real world things do change, so a system can easily fall out of sync with reality.

The main thrust of machine learning in recent years has gone in the direction of data mining, in which powerful computers ingest massive amounts of data and look for patterns. While this approach is popular, it’s risky in cases when the future might be different from the past. Investment systems built on machine learning that is not accompanied by deep understanding are dangerous because when some decision rule is widely believed, it becomes widely used, which affects the price. In other words, the value of a widely known insight disappears over time. Without deep understanding, you won’t know if what happened in the past is genuinely of value and, even if it was, you will not be able to know whether or not its value has disappeared—or worse. It’s common for some decision rules to become so popular that they push the price far enough that it becomes smarter to do the opposite.

Remember that computers have no common sense. For example, a computer could easily misconstrue the fact that people wake up in the morning and then eat breakfast to indicate that waking up makes people hungry. I’d rather have fewer bets (ideally uncorrelated ones) in which I am highly confident than more bets I’m less confident in, and would consider it intolerable if I couldn’t argue the logic behind any of my decisions. A lot of people vest their blind faith in machine learning because they find it much easier than developing deep understanding. For me, that deep understanding is essential, especially for what I do.

Just after finishing Principles, I picked up Judea Pearl's book The Book of Why and found it echoed these same ideas. Judea Pearl won the Turing prize in 2011 for his contributions to artificial intelligence around probabilistic and causal reasoning. He's credited with the creation of Bayesian networks and then built on that contribution with his models of causality. A basic message of the book is that statistics focused to a fault on correlation over causality, even while proclaiming "correlation is not causation." This led to a focus on "big data" and "data science," which can...

...tell you that the people who took a medicine recovered faster than those who did not take it, but they can't tell you why. Maybe those who took the medicine did so because they could afford it and would have recovered just as fast without it.

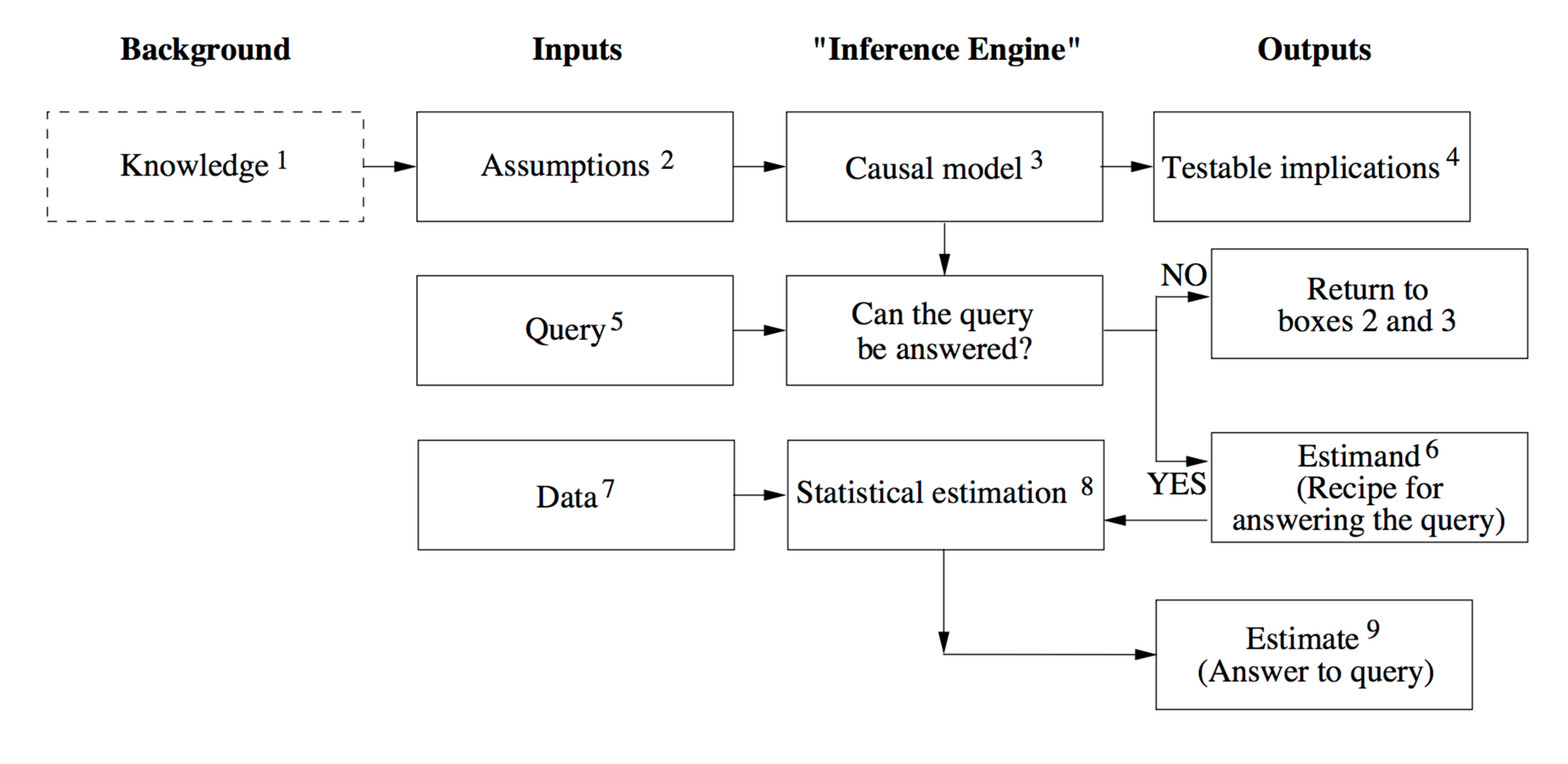

To address this gap, Pearl offers an "inference engine" that combines data with causal knowledge to produce answers to queries of interest: